The Stuff You See In Movies Is Crazy

Sam McKinniss and Michael Ovitz in conversation

spring 2021

Nu, I have not signed a release.

We’ll take care of that afterwards, Michael. Don’t worry.

Sam, how are you doing?

I feel good. Today and yesterday felt like the first couple of days when I didn't have to work on anything. I didn't have to do much of anything at all. So, that was actually very nice because it's been a long time, I suppose. I have been working on so many deadlines.

The last three days for me have felt like a party. I've been out of the house three days in a row now, and I had not seen anyone for 13 months prior to that. I’m in a state of shock.

God, that makes me sad. I relate to that though. I'm happy for you. I'm happy we’re still here.

Well, thank you.

So, how did it feel? Did it feel nice?

I felt like an animal let out of the cage. I've been incredibly disciplined throughout the pandemic. I cannot articulate how sick I got after my second vaccination shot. It did two things for me. One, it made me very sick for 36 hours, which people told me it would. Two, it made me thankful that I strictly quarantined because I couldn't have taken two weeks or more of that illness.

On a brighter note, let’s get back to Sam’s work. Where do you want to start, Nu?

Let’s start at the beginning. We have been talking about this project since early 2020, right before the pandemic began. We had lunch at Michael’s house in February 2020. It was the first time I saw anyone give an elbow bump, and it was one of my last lunch meetings… And now we're here on Zoom in April 2021. I just got my second shot today, and it feels like we’re coming full circle in a way. With that in mind, I just wanted to get Sam’s thoughts and Michael's thoughts on how these paintings came together and how the past year has influenced this particular group of works.

This is important to remember, and it's important to put this into words right now when the work is about to be seen, finally. My feeling when I was invited out to have lunch with you, Nu, and with you, Michael, was very warm. I was very excited, and I felt a lot of understanding and gratitude. And that made me feel really, very nice. And it did not take very long for that nice feeling to fade because it was immediately followed by global chaos or uncertainty and then also imminent threat. That became very confusing very quickly. However, the warmness of your invitation did not completely disappear in the midst of that.

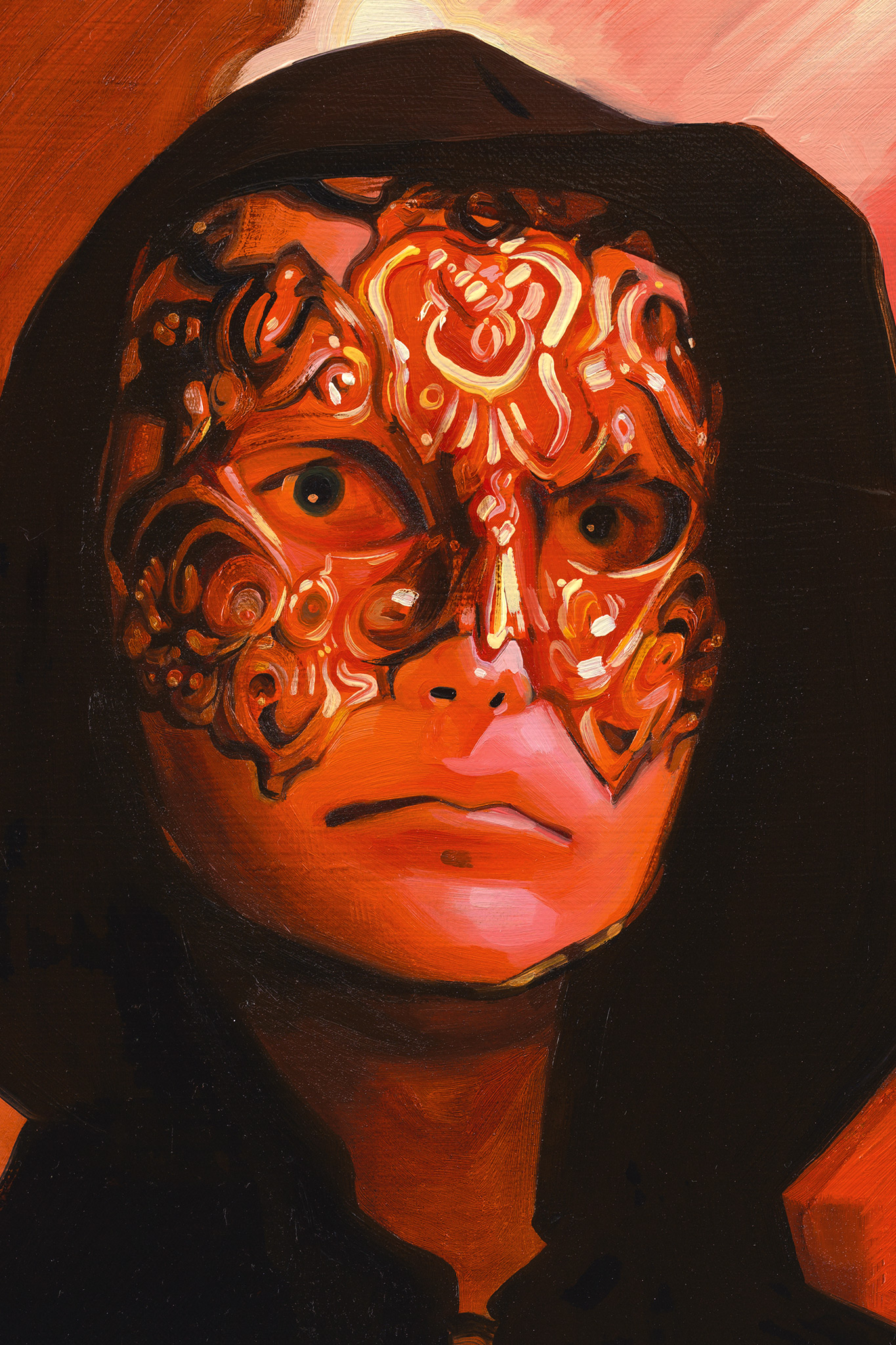

When I was getting ready to make the show, I wanted to make a contemporarily relevant show, of course, but I also wanted to try making history art. I wanted to make art that represented the time we were in but treat it like history painting. The best way I could think to do that, considering my studio practice as well as your experience, Michael, was by using language taken from “the industry.” I called the show “Costume Drama.” I wanted to make it feel portentous by using imagery borrowed from costume dramas or period pieces or things that looked like they were important to the past, while also keeping a watchful eye on the present.

My idea was, wouldn't it be amazing to recast and re-film Eyes Wide Shut all aboard the sinking Titanic? That was my initial plan. That was the only plan. It seemed a good idea to bring the orgy out from behind closed doors, like, bring the elitist, shady world of Eyes Wide Shut to first class aboard James Cameron’s sinking ship, and then let’s see what that does to my imagination. Both movies left a residue there on my memory, so let’s see what I can recollect from when I first saw them as a teenager. Combining the two films felt very 2020 in a way—like, the party was really fun, really, really, fun, and then all of a sudden, it’s all just going down the drain.

Then I was wondering, what other characters would it make sense to expand and bring into the costume party, the orgy at sea? Who else should be there? Making this show often felt very confusing and awful. And very sympathetic, I hope.

Well, I will say that you could not have conceptualized the project any better. For me, it has been an extraordinary experience because I spent my working years on moving images, and then I spent so much of the rest of my life looking at still images by painters. This project is analogous to being involved with filmmakers who would get impressions in their brain, and I never knew what would be spit back up on the screen. But the thing that moved me the most was not anything singular, but a combination of things that surprised me.

Number one, I had never witnessed someone referencing and transforming the medium I worked in, the popular medium of moving pictures, into a single image. Two, your interpretations are so vividly full of emotion. Three, the subjects are caught always in the appropriate moment. I bet if I put the directors of these films into a room with you and asked them to select some of their most important shots, you'd both be aligned on a good number of the scenes that were chosen.

The paintings are brilliantly painted, and the colors are hyper-real. The mix between figuration and abstraction at moments is extraordinary. Their blurring of time is fascinating. The paintings stand to me as both a moment in time, but also moving pictures. They're not just single frames - they remind the viewer of what happened before this scene, what happened during this scene and what happened after this scene. In other words, your still image evokes a memory that unfolds like a condensed movie. I find that to be quite special. You basically painted pictures of and about moving pictures that were still pictures that then, in turn, became movie snippets again. To me, they all resonate on a very different level, so I couldn't be happier with the group.

But I knew that about your work from the time I saw the painting of Julianne Moore that we acquired—there was a look in her face that went beyond a still photograph. It was like a publicity image, like a Cindy Sherman publicity image—the kind of things that Cindy Sherman did as she came to fame. And you did an in-color interpretation, through the McKinniss brain, of an old publicity still that goes way beyond that.

Linda

2018, oil and acrylic on canvas, 12 × 9 inches

This will be quick because I want to hear what you have to say next, but it occurs to me right now that I have you, literally you, to thank for a lot of the material I've been using to find the pictures that I want to make. I know that it wasn't ALL you, but it was a lot of you that went into making these things accessible to a person like me when I was younger. And I appreciate what you've done.

You know, Sam, I could put you into the same category as artists who do moving pictures. You just do them in a single frame. The reason is you had images impressed in your brain from watching things at any age. We don't really understand how deeply the images affect us. I mean, there's an old proverb that a picture is worth a thousand words, but I think that's inaccurate. I think a picture is worth infinite words, and I see that in your work because you take that slice of a moment in time and you bring it to life. It's like it's alive, and yet it's not being projected with light through a celluloid frame.

When Martin Scorsese did Gangs of New York, I think I told you this at lunch, I gave him a book on Rembrandt because Gangs of New York was obviously set in a period of time when all light was candlelit or daylight.

Artists have things come into their brain. Those thoughts get filed away, or they go up and back again and again. Every so often, these inventoried images come out in a painting or in a movie or in a book.

It’s also interesting to me that your works span time. For example, when I view the mountain painting, my mind travels from Cézanne to Ruscha. Your flower paintings are obviously about Fantin-Latour. Your paintings go from Old Masters all the way to Contemporary. From Titian and Tintoretto to Cindy Sherman. But you clearly have your own hand. Your ability to express lighting is unique. Most interestingly, you catch a moment. And that's what blew me away at the pictures—you paint a moment that is so defined and definitive, but also strangely mysterious. There’s an edginess and a kind of constant conflict in each image.

Well, I hope so. I like that you keep mentioning Cindy Sherman, because not a lot of people mention her to me. But it's true. When I was in art college, I would make studies of her film stills. I made watercolor studies of those to try and figure out exactly how the drama was constructed or built inside of a still image, not a moving picture, rather a still image that looks like a movie. That was very instructive to me—to copy her work just from that one series.

Instinctively, I knew that the best art I had been in touch with before I got to college was stuff that I had seen in music videos or at the cinema. In a way, the best stuff ever since then, for me, was to try and understand the process of montage, which is still image, still image, still image, in quick succession. There’s no narrative building in a dramaturgical sense. It’s just an impression of a narrative being put together by all these rapid-fire images being thrown at you, which is the experience I grew up with watching MTV. It’s something that became very impressionable with me, I suppose, and something that I've been trying to work out or work with ever since.

But it goes a step further because as human beings, our brains react from stimulus to response, and the stimulus of a single image creates a multiplicity of responses, especially when you've seen the reference material. I've seen Titanic a half dozen times, so when I look at your picture, I've seen what led to that scene and then what happens after, so I replay the movie in my head. That's why I said an image is worth more than a thousand words.

You know, it's interesting… Stanley Kubrick was a client of mine. Very few people know that. But there is a photographer who worked mostly in Europe and who had extraordinary impact on Kubrick’s work. The photographer's name was Jacques-Henri Lartigue. He was very famous in certain circles in Europe. Lartigue would catch the moment the way you do. His pictures, if you ever study them, are amazing because he captured the right moment. There were probably a thousand moments to choose from, and he got the right one.

Besides you, I think the only other contemporary artist who has kind of figured that out is Cindy Sherman, and that drove her to make her movie stills series. I assume some of the people who own those works or view them don't even know what a film still really is. Nonetheless, Cindy’s work hits a chord.

“Wolfgang” is just a movie still, yet I can remember that scene [from Amadeus]. I love that movie. I look at that painting, and I can picture what went on behind scenes. I can actually look at the image and hear him [actor Tom Hulce] laughing. To me, that’s the ultimate form of communication. By the way, just as an aside, that scene is candlelit, which is what I was talking about earlier with Rembrandt.

That painting was fun to make because I knew I had to use glazes on all areas except for the candles, so that everything but the candles would have a kind of amber patina all over it. The candles would stay very bright white and nothing else. The candles would look like they give off light, and everything else would bask in the glow.

But, I'm sorry, that's just amazing to me. I've told you this before, that I don't have much access into your world, except as a consumer. I enjoy these things. I do possess, I guess, some kind of an impressionable mind, or my imagination is impressionable. I go to watch movies or have watched movies in the past because I enjoy seeing them, but it's amazing to talk to you on your end of things. You understand how these images get made in a completely different way than I do. I'm looking at them as finished compositions, as color, as poses, as moods and whatever else is being projected at me. I love listening to you talk about them as a person who understands what needed to be done in order for me to have that experience.

Well, it's interesting. A director will work for 12 hours, which is the max they can do on set, and they will get, if they're lucky, two minutes of usable film for a movie. You will work for X hours to get to the same place, so it's a very similar kind of input. The thing that I found to be amazing is your interpretation of images that you’ve seen and how that gets spit out on a canvas rather than on celluloid. With celluloid, the director draws the shots and scenes on what's called a storyboard. You paint them. You both have the moving image in your heads, and it all ends up as something very specific. The similarities are abundant, but the styles and the art form are 180 degrees from each other. So, again, you have that tension that I find fascinating.

I was thinking to myself this morning of how to get into a dialogue with an intellectual like Sam so that I wouldn't embarrass myself, and I started to wonder what would Sam’s subjects be ten years from today? Would the subjects still be films? Or will it be streamed programs, which are technically television programs? It's obviously a question that has no answer, but it’ll be interesting to see how your repertoire develops. The good news is that you can paint anything. The cultural agenda and cultural iconography have changed and will continue to change. The delivery system has also changed. So, it'll be interesting to see what you do, Sam. What will stimulate you and what will you remember? What will influence you going forward? The idea of you sneaking away and telling a little white lie to your parents about where you're going in order to go watch Jurassic Park is a story that I love, as the person who put that movie together. Kids don't have to sneak out to watch movies anymore. They just turn on the television. It’s going to be completely different set of stimuli and motivations than we've had in the past.

I've had a little bit of difficulty with that. But maybe that's just one other thing to add to the list of pandemic reality. Yeah, I haven’t been able to go to the movie theater. Going to the movies is not the same as streaming them. It's simply not the same.

It's a completely different experience, having people fill the room.

And the enormous screen, that’s the best part. The totally pitch-black room and an enormous screen and the huge sound. There's nothing like a dark room.

I want to ask you, is there a film that you come back to and think about on a regular basis? One that you believe has had an outsized effect on how you understood the world, or how you understood yourself, or how you understood life.

I've made myself think this way, Sam, I'm just a fan. In the height of my career, when CAA handled the majority of the talent in the entire film business and 46 of the top 50 grossing filmmakers, I never thought of anything except, “did I enjoy what I was seeing.” I was less interested in the intellectual movement (that happened later, by the way) and more interested in being transported to the mind and world of another human being. I was not concerned about intellectual stimulation with film. I allowed art to do that for me. I was concerned about being entertained when watching a movie.

As an agent, I always felt that you could get the best of both worlds—you could get the aesthetic and you could get the commercial, and if you pushed them together, there was a place where they met and you ended up with something spectacular. A Scorsese movie, a Spielberg movie, Dances with Wolves, Out of Africa, Casino, Goodfellas, Schindler's List are all great examples of that. Schindler's List was an intellectual movie, a visceral conjuring of a horrific time in history, but Spielberg’s adept storytelling and meticulous attention to detail attracted a wide audience. Everyone told me Rain Man was going to fail because it was too intellectual. I said to everybody, it's not going to fail, it’s a family story. And it was the number one movie. We were told it would not do one nickel in Japan, and it was the number one movie in Japan too because it’s all about family.

I have to tell you something about that. First of all, I watched Rain Man again sometime during the last two months because I hadn’t seen it since I was young, and I was taken in all over again. Really great and just impressive. An entire world inside of that film and at the same time rather expansive. It goes lowbrow at the same time that it goes highbrow. It's excellent filmmaking.

But I have to tell you something…The last movie that I remember seeing before the theaters shut down—the last film I remember enjoying, at least—was Dark Waters, starring Mark Ruffalo. Todd Haynes made it. It also takes place in Cincinnati. My mom and dad are from Cincinnati, so I recommended they go see Dark Waters because I didn't remember ever having seen before the Cincinnati skyline on a big screen. My dad says, “that's ridiculous, what about Rain Man?” Lo and behold, there it is. I remember that skyline so perfectly from my own life, from driving over the Roebling Bridge with my grandmother and grandfather.

But what I really want to ask you is, is there a movie that comes back into your mind that you saw before you got into the business?

I mean, there were movies that I grew up with. I watched everything. I lived, as I told you at our lunch, four blocks from a movie studio. When I was a kid, I was interested in things that other kids weren't interested in, like old movies. I got my first job when I was 16 working at Universal Studios as a tour guide. But in order to prep for that job, I had to go back and watch all the great black and whites of the 40s and then all of the big CinemaScopes of the 50s, those crazy over-acted period dramas.

Orson Welles created Citizen Kane at 27 years old, and to this day, it remains one of the greatest movies ever made. A real commercial success that people thought wouldn't be was Gone with the Wind.

I'm a mega Frank Capra guy. It Happened One Night never left me. And Lost Horizon. I don't know if you've ever seen it. You have to see Lost Horizon. It's such an uplifting movie for the soul. It's from the 30s, black and white film. For a process fan like me, the movie is a triumph in filmmaking because part of it takes place in the Himalayas, and Capra wanted to show the fogged-up breath of human beings, so he shot those scenes in a meat storage facility. The stuff you see in movies is crazy. Why did I respond to Ghostbusters or Stripes or Meatballs or any of those comedies? I thank Frank Capra for that.

When Michael Crichton gave me the story of Jurassic Park, just the story, I looked back and thought about big, spectacular Cecil B. DeMille movies that I hated on some level because they were so overacted, but I loved to watch because they were challenging to make.

I always rerun old movies. I reran Ben-Hur recently. It's beyond overacted. It's kind of funny, but it's brilliant in conception for the time that it was made.

Those are the kinds of things I think about. I think about old films. You learn so much about lighting when you look at black and white films. One of the biggest fights I ever had was with the head of Universal Studios over Steven Spielberg's absolutely firm insistence on shooting Schindler’s List in black and white. They said it would never sell videocassettes because no one would buy a black and white videocassette. And here again, backing the artist paid off for me. You have to back the artist. It's their vision. Steven said to me, “I want to make this black and white film, but there's going to be one moment of color in this film, and it's at the end when you see a little girl in a red dress and that's it.” And he was right. I can't imagine seeing Schindler's List in color. It wouldn't feel right. It wouldn't feel real.

All of these tools and references go right into your work. That's why I respond so strongly. It’s impressionistic in spirit and therefore has your touch on it. It's like Barry Levinson's touch on Rain Man. That film went through four directors before Levinson did it. When your stomach meets your brain, something amazing pops out, and that's what happened to Levinson on that film. He had all the right instincts. Cincinnati was his idea.

What’s interesting to me right now in terms of art lingo, the definition of “Impression” has changed. “Impressionism” means 19th century modern French painting. But in our lifetime, “Impression” means seeing an image that makes an impact on you or your behavior. Does it impress you? Does it stick with you? Does it influence your consumer habits just for having come into contact with it somewhere on a screen? That’s a big shift in the definition of just one word from one century to our century.

Yeah. Completely different.

Sam and Michael, you both talk about the impression or residue of films, but has the residue of 2020 changed your understanding of these films that you once loved? Michael brought up Gone with the Wind. This film was actually taken off certain movie catalogs this past year. When it was put back on, introductory text and video was added to give more historical context about the film’s portrayal of slavery and the antebellum South. Sam painted the scene in Titanic when Jack draws Rose “like one of his French girls.” James Cameron is actually the person drawing the nude of Kate Winslet in that scene, and I was reminded of that power move recently when I happened upon Kate Winslet talking on NPR about the scrutiny and bullying that she endured during and after the filming of Titanic. So much happened in the past few years that I, personally, can't look at many of the films that I have loved in the same way. Every Woody Allen film, for example. Do either of you feel that way about any movies?

Immediately, I have answers to that question. I have tried, but I can't watch Kill Bill anymore in light of what Uma Thurman has come forward with about her experience making that movie. I don't feel comfortable enjoying it. I know it's a great movie, I know Quentin Tarantino is a great filmmaker, I know that it resonates with me, and I know that Uma Thurman is an amazing actor, but just knowing now what's come out about the backstory, that she was nearly killed on set, I can't enjoy it. Even though it's been one of my go-to’s.

Yes, it was on your initial list of formative movies.

Totally. But it’s difficult to get into it. Part of that is because the moment has passed—it’s not so current anymore, obviously. But more to the point, and without even knowing her, I have real affection for Uma Thurman and for her work, and that makes me feel protective of her, because I value her as a person and as another artist out there.

Lastly, what I wanted to say about 2020—I’m not enjoying this streaming thing. But on the flip side of that, there's a whole catalog of movies that I have not seen that are suddenly available to stream on the internet. They were not as easy to see before. This afternoon, for instance, I watched Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s movie The Red Shoes, which I had never seen before, but have always wanted to because it's been talked about again for at least the last 15 years.

By the way, Sam, that's Marty Scorsese’s single signature influence… to the point where Michael Powell's widow [Thelma Schoonmaker] is Marty's 50 year editor.

Right! I learned that on Wikipedia. I had never seen that movie before, but now I can watch it streaming on Turner Classic Movies. And so, while most of the new offerings that are being made to stream in the past year or so have bored me, I can watch things that I've been putting off or have been waiting to come to one of the art house cinemas or something. I can now just watch them at home.

I didn't watch much that was new this past year. Titanic totally holds up. That's a disaster movie that just has it all. It was oddly comforting during this time to be onboard with those characters, to be there with them and do it over and over again. I watched it at least four times while I was making this show. Other than that, New York just opened their movie theaters, so I did get to go see a movie last week. It was thrilling. I saw Nomadland. I avoided streaming it, so I watched it at my local cineplex.

One word, and that's Kurosawa. If you want to have fun, and you want to see the epic beginnings of many American movies, watch Seven Samurai. You'll see The Magnificent Seven. It’s just a remake of Seven Samurai.

I was really taken by Minari. I thought it was the perfect film.

I want to see that in a theater.

It's simply perfect. Talk about a family film. It's so beautiful. And the characters are just normal people, which is so damn refreshing because I feel like we only see things about rich people or celebrities now. It was great.

Nomadland did that too.

You’re right. It was similar in that regard. I also watched a lot of documentaries this year. It was hard to watch fictional programs.

Real life became too difficult to comprehend. We were trying so hard to understand what's going on.

Well, this was a great conversation with people who understand. I appreciate it. And I couldn't be happier.